The Evolution of the USMNT pathway

How the United States Men's National Team has moved away from collegiate players, and what it means for the evolving American soccer landscape

The U.S. Men’s Soccer Team’s Nations League campaign was an unmitigated failure. Seeking revenge against a Panama team that knocked them out of last summer’s Copa America on home soil, the Stars and Stripes lost for the third time in the last four attempts against the Central American nation.

One of the few bright spots, however, was 24-year-old forward Patrick Agyemang, who scored his third goal in just his fourth game for the national team in the 3rd place playoff against Canada.

As the commentators and media never failed to remind us, Agyemang came a long way to be there. After all, the Charlotte FC forward was playing for a DIII college program as recently as 2019.

But what many fail to realize is that while the division makes it even more impressive, it’s the very fact he played collegiate soccer that makes him stand out.

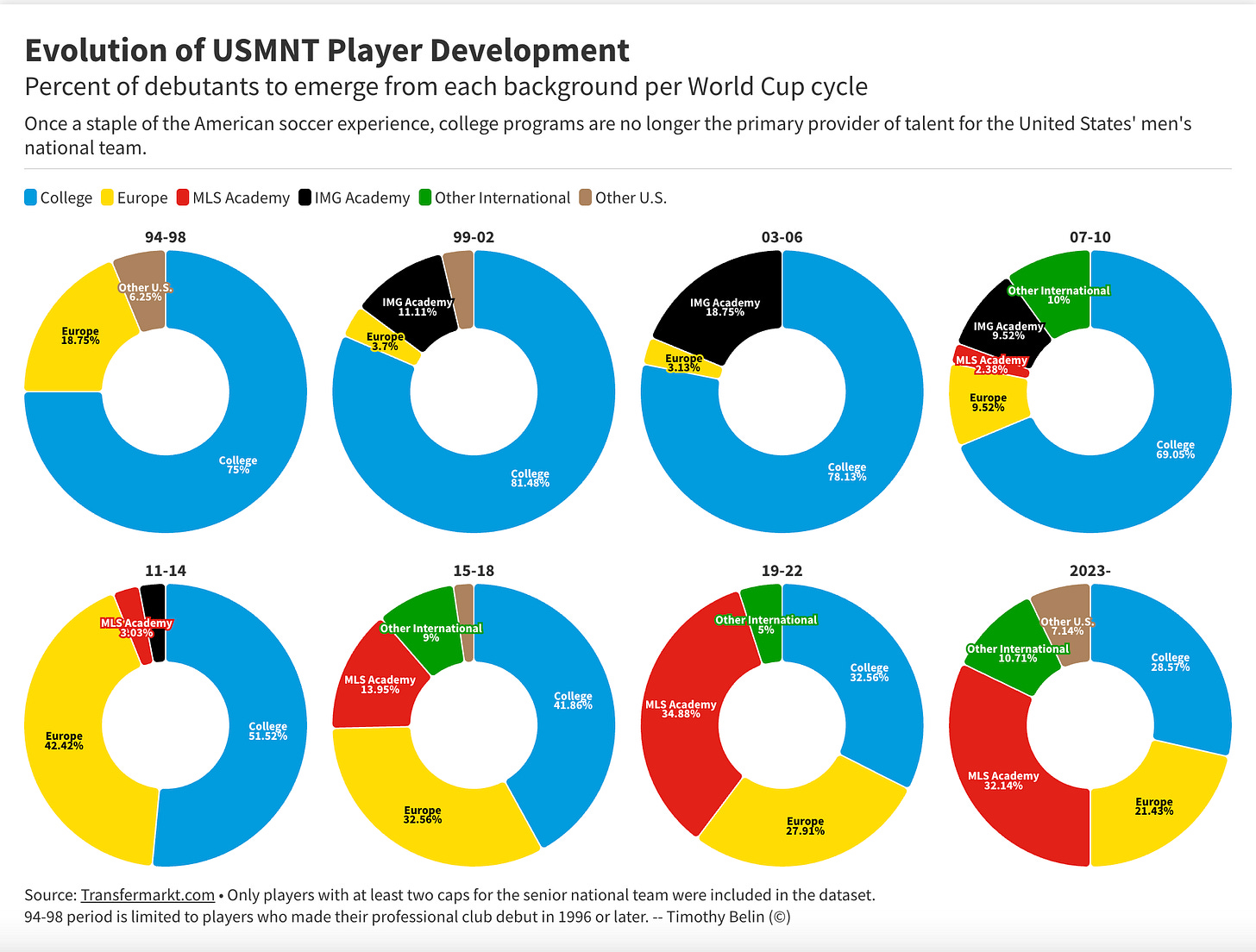

In a country where college sports have long been, and remain in every other major sport, the precursor to a successful career, soccer has been steadily moving away from that model. Though over three-quarters of the national team were made up of college alumni for most of its existence, that number has consistently fallen for the last two decades.

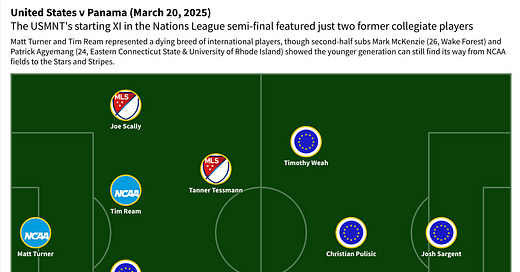

Of the 22 different players who saw the field against Panama either last week or last summer, only four had prior experience competing in the NCAA.

“The development pathway has expanded, plain and simple, beyond college,” said Russell Payne. A former collegiate and professional soccer player, Payne now coaches Northwestern University’s men’s program while also serving as an assistant for various levels of the national side. “I will not say college is not part of the development, but it has expanded and it’s one particular pathway that used to be primary and now it’s becoming more of a secondary pathway, or a parallel pathway.”

“The development pathway has expanded, plain and simple, beyond college.”

- Russell Payne, Northwestern University men’s soccer head soccer

The reasons for this change are twofold.

The introduction of MLS academies, youth set-ups ran independently by each Major League Soccer franchise that compete against each other in the MLS NEXT league, has created direct competition for the college pipeline. And many players are also risking their chance in Europe at an earlier age than before.

Since 1996, when Major League Soccer hosted its inaugural season, 264 players have made their international team debuts and gone on to play at least twice for the USMNT. More than half, 145, have come from a collegiate background. But since 2010, when New York Red Bulls’ Juan Agudelo became the first product of an MLS academy to represent the senior national team, those numbers have dramatically shifted.

The 1999-2002 World Cup cycle, the first full cycle following the league’s establishment, saw former college players make up over 80% of the USMNT’s debutants. With every subsequent cycle, that number has fallen, down to just over a quarter for the current four-year period.

MLS academies have seen an opposite trajectory in that time frame. When Agudelo broke through in the 07-10 cycle, they formed less than 5% of national team debutants. In the past two World Cup cycles, dating back to 2019, they have grown to consistently making up one third of newcomers.

John Gall, longtime coach in the FC Dallas academy and current head coach for North Texas SC, Dallas’ MLS NEXT team, said the advantages of an academy are obvious. Players are brought up in-house, where they learn to play the same style and tactics as the first team, making for an easier transition from youth to professional.

Since establishing its academy, FC Dallas has been the most successful MLS side at producing talent for the national team, with eight such players emerging directly from its ranks. That’s without counting alumni such as Weston McKennie, Shaq Moore and Chris Richards, all of whom had stints in the Dallas youth setup before joining European academies to complete their development.

However, despite his interest in keeping all his best prospects at home, Gall said he still sees value in the college path.

“Even we feel sometimes it’s important for a kid to maybe move away from home or go to college for a couple of years and kind of find yourself and become an adult and all those things, and then come back to becoming a professional footballer,” said Gall, who, as a Welshman, still refers to soccer as “football” despite living in the States for over two decades.

“Obviously college football is not quite exactly like it is in academies, and in MLS NEXT pro teams where we’re trying to follow the pathway of the first team, so there are some differences,” he continued. “But we feel that sometimes the psychosocial development of players when they go to college is an important piece too.”

Gall isn’t the only one who thinks colleges still have a role to play.

Sasho Cirovski, head coach for the University of Maryland since 1993, has produced 12 players for the senior U.S. national team, second only to UCLA among colleges. Cirovski said that the U.S. imitating the European academy system is crucial in catching up to the major soccer nations south of the continent and across the pond, but he added that there are still some advantages only colleges can provide.

“One of the things that some of the European teams have told me is that they’re very impressed with the quality of character that they get from the kids who spent a few years in college,” Cirovski said. “There’s a lot of talented players in Europe that never make it their first season because they don’t have the nurturing support that you might have in the first few years in college.”

“European teams have told me […] that they’re very impressed with the quality of character that they get from the kids who spent a few years in college.”

- Sasho Cirovski, University of Maryland men’s soccer head coach

That support, at odds with the harsh reality of professional sports, is one of a few cards college still holds to its advantage.

The other is that player development is rarely linear.

International stars such as France’s N’Golo Kanté and England’s Jamie Vardy are prime examples. Both were virtual unknowns before breaking out in their mid- and late-20s, respectively, for Leicester City. Since then, Kanté went on to become a key member of both France’s World Cup-winning team in 2018 and Chelsea’s Champions League-winning team in 2021, while Vardy established himself as one of the most reliable goal scorers in the best league in the world.

Looking closer to home, Chris Wondolowski is a name that quickly springs to mind.

The American forward made his USMNT debut in January 2011, just six days shy of his 28th birthday. Drafted in the fourth round of the 2005 MLS Supplemental Draft by the San Jose Earthquakes, he originally struggled to establish himself in the MLS with either the Earthquakes or his next team, Houston Dynamo. In his first four-and-a-half years of professional soccer, he made just 39 league appearances, 28 of them as a substitute

But after returning to San Jose in the summer of 2009, something clicked for Wondolowski. Starting in 2010, he won two MLS golden boots, was the MLS MVP in 2012, led the USMNT to the 2013 Gold Cup as the competition’s top scorer and made the national roster for both the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Copa America.

He retired in 2021 as the MLS’ all-time leading goalscorer.

“You have early developers, you have late developers, you have players who are performing really well but maybe they don’t quite have the projection to be a pro,” Gall said. “All of this is a very delicate mix of getting it right and understanding when to push players forward, when to hold them back, when to allow them to make mistakes, allow them to be free, and all of these things.”

“All of this is a very delicate mix of getting it right and understanding when to push players forward, when to hold them back, when to allow them to make mistakes, allow them to be free, and all of these things.”

- John Gall, North Texas SC head coach

While a lot of focus is often given to young superstars, with Philadelphia Union’s 15-year-old starlet Cavan Sullivan just the latest example, Payne advised against expecting them to be anything other than a rare exception.

“You don’t see it every week, but they really consume the narrative,” he said. “They are so far outside of the norm, but we talk about them as if that’s the way things should be going. I completely disagree. I think they are special and they should be respected as special and different.”

In contrast with this focus on youth, college offers the opportunity for late bloomers to mature at their own pace and still get a shot at a professional career. For Jared Embick, head coach of the University of Akron’s men’s soccer program who oversaw the development of six USMNT internationals, keeping that avenue open is a must.

Though he no longer believes colleges will be expected to produce the biggest names in American soccer, Embick said there is still immense value in serving as a safety net that can expand and strengthen the existing player pool.

“We’re just trying to strengthen the player pool, and if you give up early on kids, at like 20, 21, you’re going to lose the ability to maximize your player pool for all your leagues,” Embick said. “Even if it doesn’t help the national team, it helps make more depth for the league and championship. If you have a better USL Championship, then you can send players on loan from the MLS to get a better experience that maybe speeds up their development. So I’m thinking about how you maximize your ability to strengthen everybody.”

“Even if it doesn’t help the national team, it helps make more depth for the league and championship.”

- Jared Embick, University of Akron men’s soccer head coach

Embick isn’t wrong. While colleges no longer produce international players at the rate they once did, their contribution to the country’s top division has remained a constant.

From the MLS SuperDraft’s inception in 1996 to the last pre-COVID draft in 2020, MLS teams selected 1,467 picks. Two-thirds of them went on to play at least 1,000 minutes of professional soccer, with that number reaching closer to three-quarters from 2015 onwards.

The lack of former collegiate players in the national team is thus a reflection of the increase in talent in the national pool rather than a mark to be held against colleges.

In addition, Embick is right to be concerned about players slipping through the cracks, as American professional teams are in no way equipped to cover the entirety of the U.S.

MLS currently has 30 teams, with a couple more potential expansion teams in the pipeline, while the United Soccer League has 38 professional outfits across the USL Championship and League One.

That’s just 68 professional sides to cover the whole of the United States.

In comparison, England, a country nearly three times smaller than Texas, has 96 fully professional teams competing in its top four divisions, with many more pro sides bouncing around the National Leagues. It’s therefore no wonder that American players can have a tougher time breaking into elite academies than their European counterparts, and struggle for game time once they’re there.

With regular minutes one of the most valuable commodities for a young player, college becomes an attractive offer once again when considering these numbers.

Nowhere is it more noticeable than for goalkeepers, a position notoriously difficult to break into.

Because there can only be one goalkeeper on the field at any given time, and because they are less likely to be rotated due to fatigue, goalkeepers tend to break through at significantly later ages than their outfield counterparts. So it should come as no surprise that theirs is the one position still heavily benefiting from the college setup.

This past week, all three goalkeepers on the USMNT’s Nations League roster emerged from a college team. 10 of the 14 other twice-capped keepers to have made their international debuts since 1996 can claim the same.

“Goalkeepers in this country have historically had quite a bit of success because you mature a little bit later in terms of your understanding of the game and your application,” Payne, a former goalkeeper, said. “And goalkeepers need minutes. So it really applies to goalkeepers really specifically too, where if you play 60 games in college in a three- or four-year period, you most likely were not getting 60 games as a 20-year-old [for a professional team].”

With the college pathway still proving viable, establishing a stronger connection between MLS and colleges could therefore prove crucial for the future of U.S. soccer. Though NCAA amateur rules currently restrict any outright partnership between the two, some changes are on the horizon that could already make significant differences in keeping the college pathway attractive.

For over a decade now, Cirovski has been lobbying to change the college soccer schedule, and the end might soon be in sight.

NCAA soccer currently takes place exclusively during the fall, packing in 25 to 30 games in just 15 weeks.

“It’s an archaic playing and practice season mode, it’s very unbalanced in terms of both experience and development,” Cirovski said. “It’s something that needs to change and there’s not a day that goes by that I don’t work on changing it.”

“It’s an archaic playing and practice season mode, it’s very unbalanced in terms of both experience and development.”

- Sasho Cirovski, University of Maryland men’s soccer head coach

Cirovski, Payne, Embick and many others believe it would be better to spread out the season over the full academic year, with a winter break, to mirror the demands of professional soccer leagues around the globe. With changes currently taking place in the NCAA landscape on a number of fronts, Payne said he thinks the time has come where they might finally get their wish.

If they do, that would be the first step to what all three coaches believe college soccer can ultimately become: a highly competitive reserve league for the professionals.

With the NCAA beginning to relax its restrictions on amateurism, and conference realignments taking over the college football world, Payne said there is an opportunity for soccer to follow suit and take advantage.

If the best collegiate players can all play against each other while also earning some revenue in addition to their degree, Cirovski said collegiate soccer could become “the best platform for 18- to 23-year-olds in the world.”

“College is still a great place for guys that could be late developers, could have maybe been overlooked because they maybe couldn’t afford to play in the best league in the country,” Embick said. “We can still be part of the developmental pathway, and if everybody wants to work together it could be better than what it is currently.”

Big changes are undoubtedly coming to the American soccer landscape following the USL’s recent announcement of a Division I league and promotion/relegation. It seems a perfect time to simultaneously redefine the role colleges can play if the United States truly wants to become a soccer power on the international stage.